Facebook Posts

This strikes me as a very useful suggestion from Jack Henneman. And home educating parents could do worse than setting their high school students to study for the naturalization exam.

What do you think?

**

I would not make a high school diploma turn on passing the naturalization test. That opens a very smelly can of worms - the federal government setting specific graduation requirements for public school students. I think that is a bad idea that could go all sorts of ugly places. Imagine the politician you most deplore with that power, and perhaps you’ll see it my way.

However, I (obviously) think it should be national policy to reinvigorate the teaching of civics. It was a big mistake to all but abandon it, and we’ve paid the price in the degradation of our national discourse and quality of our political leadership.

If I were making these decisions in the Trump administration, I’d propose simply requiring that public schools demonstrate that 75% of their graduating seniors have passed the naturalization test in order to receive any federal funds.

Of course, give schools a few years to catch up. Suggest they administer the test to 10th graders, and then re-administer it to those who fail it the next two years. Otherwise, do not dictate how to teach civics, or whether the diploma should hinge on it. That would do nothing more than provoke the usual thermostatic reaction, with the inevitable counterproductive result in the end. Tie a reasonably high pass rate to federal funds, however, and public schools will have all the incentive they need to make sure their students are at least up to the standard we demand of new citizens.

**

open.substack.com/pub/jackhenneman/p/leveraging-the-us-naturalization ... See MoreSee Less

2 days ago

- Likes: 88

- Shares: 3

- Comments: 23

I'd like to see candidates for every federal office be required to pass the test, administered by an impartial proctor. I am not confident in our leaders' knowledge of our constitution or history.

I teach a citizenship class for immigrants going through the naturalization process. I am also a former K12 civics (and other social studies classes) teacher. The danger of relying on the naturalization test is that it can be changed by each administration. (Now 128 questions instead of 100 and geography questions removed, wording changed, etc. Also, there are questions in it that are deceiving and in some cases not factually accurate. (For example, crediting Abraham Lincoln with freeing slaves with the Emancipation Proclamation, but that is definitely not the whole story…hello…13th Amendment anyone?) For something that should be objective, in some instances it really seems subjective and based on current administration’s whims. And I vehemently object to tying testing to federal funding. The places with the lower scores often are in need of the most funding. I think there’s room for teachers to use it as a tool as I have in the past, but it’s simply one tool. Some states have a civics knowledge graduation requirement and I think that can be accomplished in other ways, not with high stakes placed on one test.

As a former public school kindergarten teacher, I understand the idea but know that it would never work as it aspires to. Federal funding is already distributed in the wonkiest of ways. Districts already impose crazy hoops for schools to jump through. And administrators already strain teachers to the point of breaking. Now, you get some big publishers like Pearson (I hate them and liken them to the devil but that’s just me) or McGraw Hill to prioritize civics across subjects in all grades, and you will see a difference. Especially, if you can incentivize them without punishing teachers. Mostly, I think people in offices should leave people in classrooms alone. Unless, you are covering a bathroom break or subbing, leave teachers alone. The vast majority know what and how to teach, but office people keep adding/changing/subtracting curriculum with no regard to real life and real kids.

My husband is a naturalized citizen. I think the American child should aim for a bit more than the very minimal knowledge of our country required to pass that very easy exam.

15 years ago I studied with my husband for his naturalization test. I have helped students (adults who immigrated) also study and find the materials they needed. This author is dismissive and rude about the old test and wishes an even harder test on people who actually had/have to study and memorize 100 (now 128) questions as they have no idea which 20 (previously 10) they'd be asked. It is an important test and I don't think he feels this way at all. Here is the quote that made me angry: "The new questions are not obviously more difficult than the old questions - both are almost laughably easy to any reasonably educated American, and certainly anyone who reads Substack posts. Perhaps more difficult questions are coming in a subsequent revision. I hope so." Learning 128 facts and hoping the ones that stuck with you will be the ones asked is hard. It can be done by most students and I like the idea of high schoolers studying and taking the exams. I do not feel that federal funding should hinge at all on the test results. None of it is "laughably easy." Most Americans are not "reasonably educated" or in need of leveling up - just start with what is already required and help the students learn.

My oldest kid took a homeschool co-op class in government and the kids all took that test at the end of the course. They passed. It was a good addition to the course. I think it could have a place in public schools, but I hate forcing teachers to use a specific test and making scores tied to funding.

I gave my oldest the list of questions provided on the website for naturalization. There were 100 questions. She answered all of them over the course of her senior year. It was a part of her civics credit for the year. I’ll be doing it with my others as well.

That is an interesting idea. I find it rather hypocritical that we expect aspiring citizens to reach a standard of knowledge to which we refuse to hold ourselves as citizens.

As someone naturalized over a decade ago, I recall the naturalization test being pretty easy. The difficulty level was akin to the driver's license written test. Even easier, I believe. I don't imagine it would be too much of an obstacle for anyone who makes an honest effort.

Massachusetts still requires Civics, even for homeschool students. I can't understand why any state would skip that.

An Afghani friend and I put together a video series to help Dari speakers study for and pass the citizenship exam. It was quite educational to do so with an immigrant collaborator.

We did the 100 questions as a morning time activity a few years ago. Probably time to revisit as my younger two are now 11 and 13 so the lessons of years past will have faded. I think it’s important to have the US civic basics in our heads, just as citizens—obviously more so now when the Constitution faces so many challenges, but also in solidarity with immigrants.

My daughter and I studied all the exam questions together last year for her 8th grade year. I think it’s a fantastic suggestion for everyone—school kids and adults alike!

I printed the questions and plan to mae sure we can answer them all. I feel like if we expect those applying for citizenship to do it, then we should as well.

I think that they're only asked up to 10 questions, and they only have to get 5 correct, but still not a bad idea.

I go through it after the government class in our homeschool co op. Why not? It’s a test with real consequences for many people. We don’t see many tests like that. Also- it isn’t rocket science. It is 100 civic short-answer questions. A kid who paid attention in a decent government class should be able to answer most. The official takes ten questions at random and asks them. Only six need to be answered correctly. The kids having it in their recent memory isn’t the problem. It’s the adults twenty years later who forgot most everything they ever learned in that subject and more because they didn’t appreciate knowledge.

I had high school civics in the 1980s in Kentucky and was surprised when a course so fundamental was abandoned. I went on to receive a MPA so I'm biased but a run through governance is critical for all. I do wonder how this would look for the classical school purists who favor history over social studies.

I am not against Civics in school. It would be very helpful to learn it, after all, we have politicians in the Government who think the three branches are the Executive, the Senate, and the House. There are a lot of people walking around now unaware of why there are different tax breakdowns and what they cover, and that's their money! BUT I'm not sure any more of the Government giving this test, given how partisan the country is at this moment. It would have to be an agency that is a lot like the the Fed. I don't agree with tying funding to it either. We've all seen wild swings in how schools are funded, some that have never seen a basic science kit, and others who have cutting edge technology, and those students are not educated the same.

I studied for and took the test for my own naturalization process, then taught it in a classroom setting to immigrants in the process of naturalizing. I also homeschooled my children for 17+ years. If high school seniors cannot answer all 100 questions - not because they may have forgotten some answers, but because they were never taught - their social studies, civics, or US history curriculum was lacking in the first place. If immigrants are expected to know the answers to all 100 questions (with no guarantee which ones will be on the test), so should American citizens by birth.

I think we should administer it to every elected politician, and every appointee. Then fire everyone who doesn't pass! 😁

Not strictly civics, but inclusive of instruction in community structure and participation, the Junior Achievement program is available to any citizen to use in educating children. During the three years my son was in public school, I found a couple of teachers who agreed to let me bring a module to their class. That was over 25 years ago. I have not looked at the content since, but it is still an available resource.

Florida is paying its educators $3,000 to take a 55 hour online civics course. Home educators are eligible. I’d love to know what the course looks like. Anyone here in Florida? www.civicsliteracy.org/civics/course

Great idea for homeschooling. Terrible idea for public schools. There’s no better way to encourage people at every level to cheat, teach to the test, and degrade the value of both the test and the class than to tie it to funding.

I saw this piece by Daniel Walden on THE POINT a few weeks ago, and am delighted to see it reprinted in THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION.

You may absolutely disagree with Mr. Walden's political or cultural convictions, but please do read through the whole piece, and see if you resonate with his conclusions. I certainly did--because they have nothing to do with being "left" or "right", and everything to do with being human.

**

...[D]espite our eggheaded reputation, the American left has failed to articulate a broad and unified vision for education. We are generally successful at toeing a line on issues of policy — robust funding for public education, opposition to charter schools, strong support for teachers’ unions, etc. — but the left, having painted a compelling and persuasive picture of a political life that should empower ordinary citizens and of a working life that ought to be a source of pride and dignity, has not been able to make a similar case about what education is for.

As a leftist myself and a university professor, I find this failure particularly galling — especially at a time when the various symptoms of postindustrial capitalism have leeched away the university’s public financial support, pushed students into ever-narrower vocational training for ever more uncertain job prospects, and so inflated tuition rates that a four-year degree can cost as much as a three-bedroom house. What is being offered as education is so far removed from any recognizable articulation of the good life that an alternative is not merely desirable but necessary for education to be considered part of the good life at all.

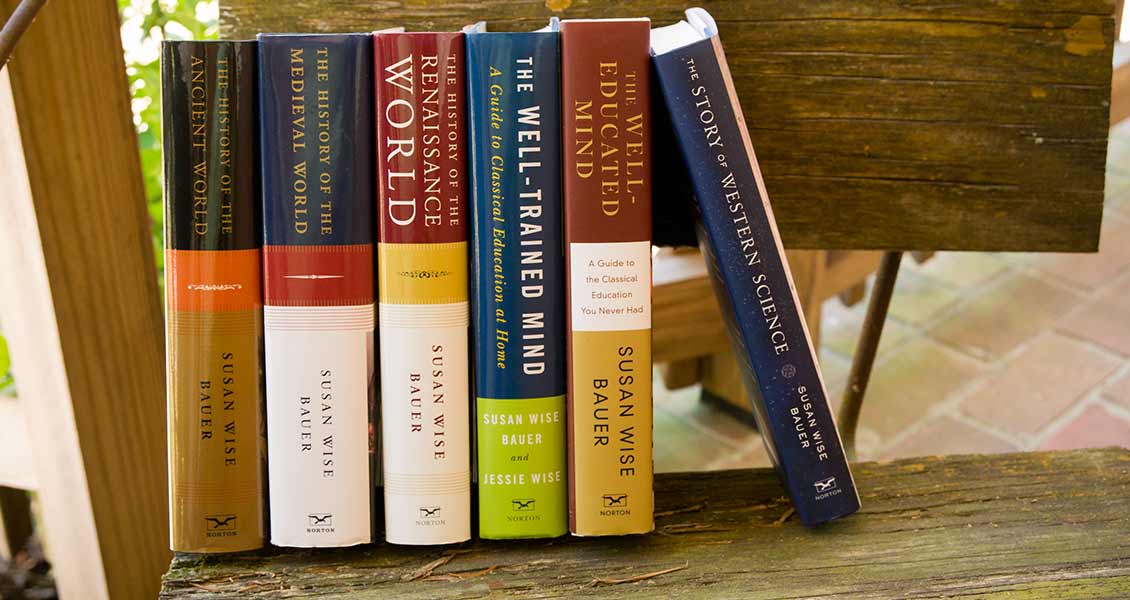

The American right also recognizes that there is a crisis in education — and has responded to it in a variety of ways. The most substantive of these responses generally goes by the name of “classical education,” although the term encompasses a great variety of visions and practices. In some cases it seems to mean nothing more than a preference for old books and discussion-driven teaching; in some it puts a Montessori-like emphasis on creating a beautiful and stimulating learning environment; and in others it decries liberalism, communism, and gender theory as the harbingers of social collapse. The movement’s contemporary shape and name can be traced back to Susan Wise Bauer’s 1999 book The Well-Trained Mind: A Guide to Classical Education at Home. Bauer’s book views the medieval trivium — grammar, logic, and rhetoric — as a framework for moving cyclically through subjects as a child matures: first learning a subject’s basic elements and how they fit together (grammar), then learning argumentation and causality and abstract thinking across various domains (logic), and finally how to make arguments that are elegant and persuasive in addition to being valid (rhetoric). The various practitioners of and advocates for classical education share a commitment to teaching accepted canonical texts (drawing largely on the “Great Books”), to education as inseparable from character formation, and to the thesis that the abandonment of the two prior commitments by K-12 schools and universities has hollowed out their ability to effectively educate students. Many proponents of classical ed draw on the ancient distinction between liberal education, suitable for free persons who are to govern themselves and others, and servile education, suitable for those who are to be useful to others, noting that education in a democratic society ought to prepare all people to lead meaningful lives in pursuit of a vision of the good, not merely to work as someone else’s employee or to serve a particular social function.

Education like this, based on “great books,” has a somewhat unsavory reputation on the left. This is due, in part, to its recent association with conservative or reactionary political movements. It’s also because we do not wish to be elitists or chauvinists. Great-books advocates have been guilty of both; it is all too easy to slip from reading things because they are recognized as good to reading them because they are merely recognized....

Yet the underlying theses of classical education do not strike me as baseless, nor even particularly right-wing. I have always found the distinction between liberal and servile education to be compelling, and the idea that value-free education is desirable or even possible strikes me as absurd on its face. The notion that students should mainly be acquiring “skills” or “competencies,” so prevalent in high-level discussions of education policy and in ranking school systems, rings hollow to anyone who has ever cared enough to become a teacher: One teaches because one has fallen in love and, like any lover, one wants to shout it from the rooftops, because in loving something we come to see that it is good, that it is something a person should want for themselves. We on the left generally agree that education is for the student’s benefit, not for the benefit of their future employer, and that students go to school not merely to acquire skills but to develop an entire social and intellectual life: to have something good and to have it forever. We are sometimes embarrassed to say this, I think, out of misplaced or excessive courtesy: We have seen too many snobs tell people what they ought to like. But we shouldn’t be. It is not snobbish to say that a person with lungs must breathe or that a person with a stomach must eat, nor that a person with a mind must think. It is not snobbish to show someone how to love something new — it is a gift...

We are very far from the world that we on the left would like to live in, the world in which simply living is possible for everyone, and building that world demands difficult work. But it also demands thought, and perhaps we can carve out a little bit of time to think and rehearse for a world in which we can all be more human. If you do not believe that it is possible for someone’s life to be changed by reading and thinking together then I wish you well, but I do not think we are in the same profession and I am not sure we’re on the same side. I can tell you that some years ago now, a young man who was still a convinced atheist read Augustine’s Confessions and found in its pages an account of evil and responsibility that overturned his entire moral picture of the world. That same young man took in Plato and Machiavelli and Hegel and Marx in great gulps the following year and felt like he had fewer and fewer solid places to stand but a much better sense of where he was.

**

www.chronicle.com/article/the-left-wing-case-for-great-books

thepointmag.com/examined-life/the-left-case-for-great-books/ ... See MoreSee Less

The Left Case for Great Books | The Point Magazine

thepointmag.com

A great-books model at the undergraduate level is, in fact, so consonant with Freire’s radical critique that it represents a far better path forward for a left-wing vision of education than virtually anything else currently on offer in the United States.4 days ago

Thank you for sharing! Very well said. I really hope more and more people across the political spectrum will recognize that education should not only prepare people for job functions. At a minimum, it should prepare competent citizens, participants in civil dialogue, and life-long learners.

Well, that was unexpected (in the most delightful sense). “Books programs is not only the syllabus but the intellectual community that is formed. A community is necessary because it lets people who have begun to recognize their common humanity develop new ways of relating to one another that have nothing to do with the scripts handed to them by their social context, and this new community must be insulated in some way from society at large so that the compulsion to follow these omnipresent, ready-made social scripts loses some of its force. I might be accused here of advocating that students be put inside a bubble and disconnected from the real world, and I would answer that yes, that much should be obvious. It is precisely the world, understood as the social and economic structures into which we are born, through which we secure the necessities of survival and which hedge the boundaries of our social worlds, that an educational community must shut out, for the same reason that a monastery must do so: There is common work to be done that demands the cooperation of free and equal human beings.”

“These are not questions to which any honest instructor can pretend to have a definite answer: they demand serious thought from many people who can take one another’s ideas and test them or turn them in a different direction. In this way, the contributions of each student help their classmates step into larger, more thoughtful versions of themselves: like my students did on that post-election morning, they step through and beyond their present concerns into what they didn’t know they needed. They see more sides of the question; they take in a greater share of humanity; they are, in Freire’s understanding, more free” (Walden). This is one of the things I love most about education and open, honest discourse. It can change lives. Great read. Thank you for sharing.

"One teaches because one has fallen in love and, like any lover, one wants to shout it from the rooftops, because in loving something we come to see that it is good, that it is something a person should want for themselves." Beautifully said.

One of my must read journals.

Thanks for sharing. The Great Books are awesome for a solid educational foundation.

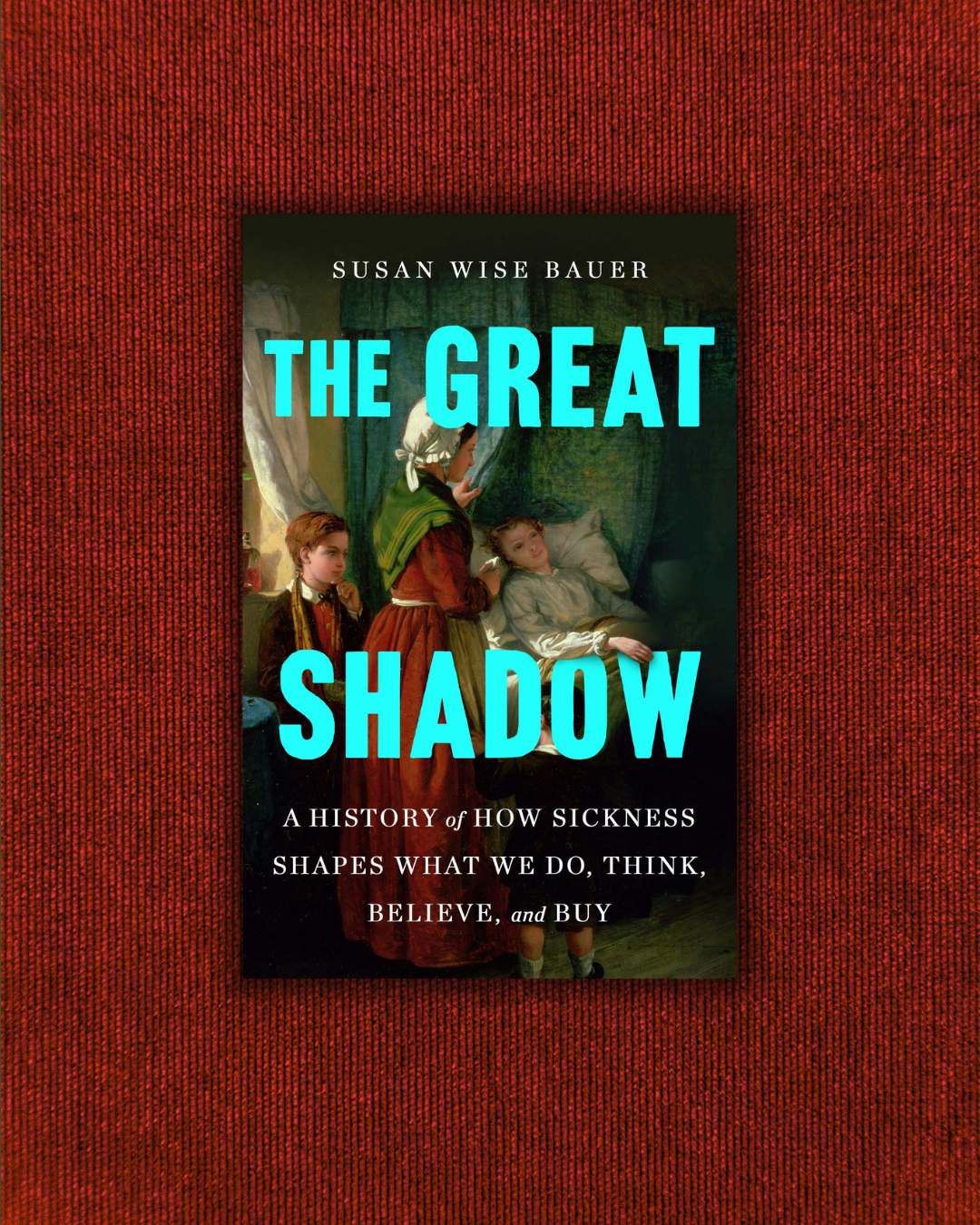

If you're in the Williamsburg (Virginia) area, come by this afternoon for my book talk at William & Mary's Swem Library! ... See MoreSee Less

This content isn't available right now

When this happens, it's usually because the owner only shared it with a small group of people, changed who can see it or it's been deleted.1 week ago

Loved your book! It's interesting how folks today remain divided between science and magic. I suppose it's so easy to believe in what's simple and it doesn't help when the powers that be, force science in times of crisis. I'm a scientist and so far have always chosen to vaccine-up. As one example that you pointed out, it becomes complicated in places such as mandated public education (K-12) when we must seek to protect our students who not only transmit the disease to other students but ultimately their families and friends. Thank you for getting both my synapses firing at the same time. It will be interesting to follow the current measles outbreaks to see what the government does.

Oh, I wish I lived nearby! Really enjoying the book!

I'll be the one in the back of the room, raising my hand and asking simple questions like, "what is love?" and "what's more fun to have--cholera, or dysentery?"

Congratulations

I hate missing your talk today! Congratulations on your new book and thanks for being one the the firsts to present in the Makenzie Theater at W&M Libraries

I wish! Already using some facts from it in class. Great for discussions with my Classical Greece class.