Facebook Posts

Neither snow, nor sleet, nor freezing rain will keep the dufus heads from their appointed rounds. ... See MoreSee Less

13 hours ago

- Likes: 43

- Shares: 1

- Comments: 7

Living the life! I miss those mornings! My old two passed 3 and 5 years ago at the wonderful ages of 34 and about 31! Miss them both so much! This was my Keystone, aka, Ruling Ruler (appendix registered), grandson to Secretariat. He was my barrel horse back in the day and then became my husband header partner.

Awe! They are great. I miss my American Paint so much.

Love it!

They are beautiful ❤️

Beautiful and invigorating.

At least someone is enjoying the weather! ❤️

Very happy “Dufus Heads” ❤️They probably enjoy that their footsteps are so noisy. 😂

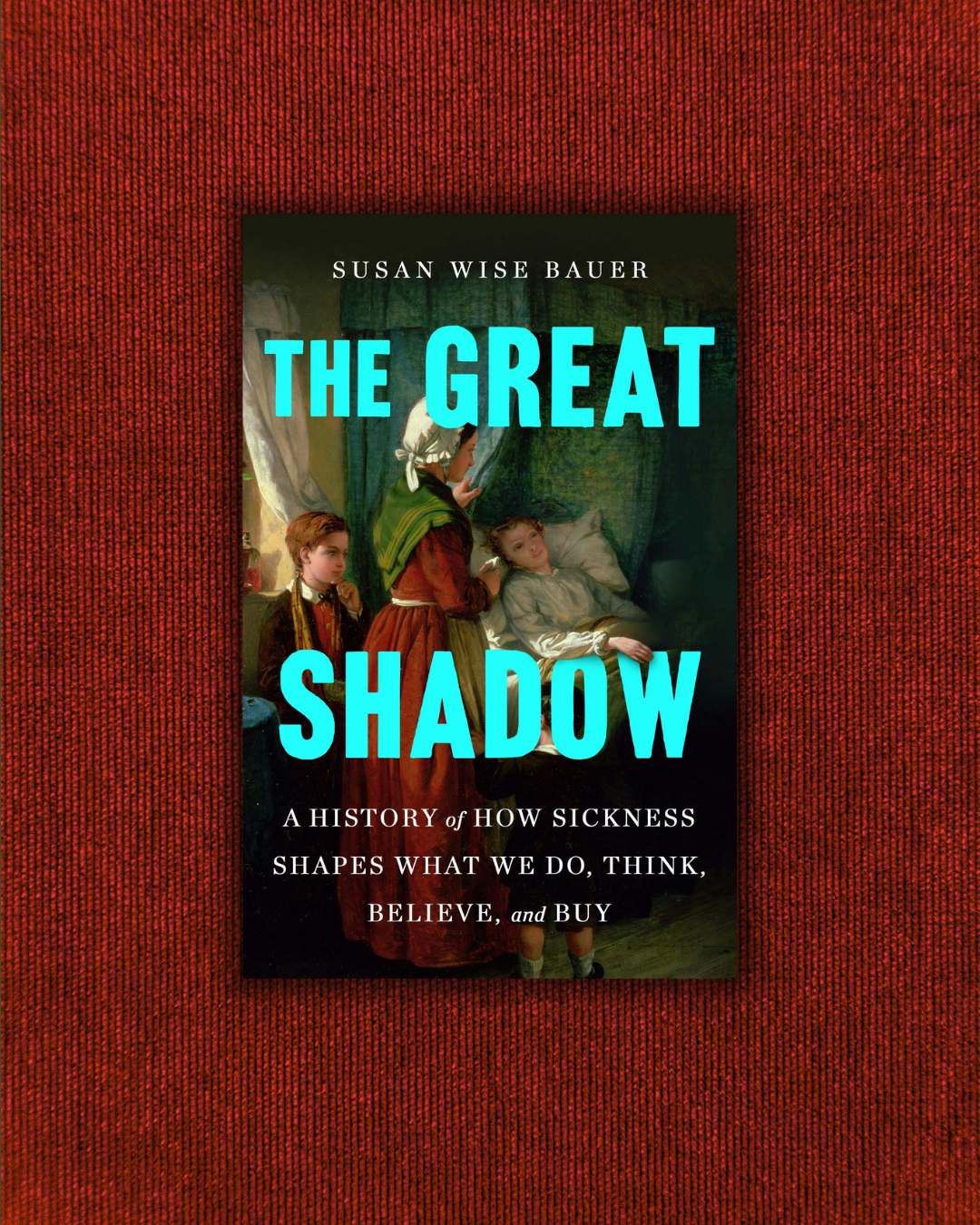

Two big events over the coming week--the pending icepocalypse (I'll let you know how that works out), and the publication date on Tuesday, January 27, of my new book THE GREAT SHADOW: A History of How Sickness Shapes What We Do, Think, Believe, and Buy. I am distracting myself from the upcoming loss of power with the two newest reviews. The New York Post writes:

"Our evolving theories about what makes us sick haven’t just changed medicine, Bauer argues in her sweeping history. They’ve shaped civilization itself, influencing our religions, political systems, consumer habits, prejudices, and even our understanding of the universe."

And the Wall Street Journal says:

"It is easy to forget that, even in today’s healthiest countries, we are only four or five generations removed from a world where most people, most of the time, died of infectious disease...Ms. Bauer reminds us of the human dimensions of living in such a world...'The Great Shadow' benefits from Ms. Bauer’s keen sense for the way the bodily experience of disease so readily takes on psychological and spiritual freight...Ms. Bauer winsomely threads scenes and vignettes from contemporary life throughout her book, especially from our polarized landscape, still haunted as it is by the Covid-19 pandemic. Often, the point is to contrast how fortunate we are to live in a time when not every sniffle is a herald of doom, nor every cut and scrape a portal for merciless bacteria to enter and feast on our flesh. The author appreciates what a terrific advance modern germ theory represents, but she also recognizes its tendency to generate absurd excesses. Her history of Kleenex tissues is a tour de force."

Why, thank you, I immensely enjoyed writing the history of Kleenex. It was, unexpectedly, a place where a number of different threads wove together into a pattern.

Enjoy the reviews, and, if you're feeling like it, order a copy.

www.wsj.com/arts-culture/books/the-great-shadow-review-sickness-and-civilization-e7fa2ad5?st=mSvZ...

nypost.com/2026/01/17/world-news/sickness-changes-the-way-we-actually-think/ ... See MoreSee Less

How sickness changes the way we actually think

nypost.com

“As we investigated the causes and cures of sickness within us, we began to change our views of the universe outside,” Susan Bauer writes in her new book.5 days ago

I'm so excited to read this!

Got mine today!!! Looking forward to it.

Mine came in from my local independent bookstore in Sarnia, Ontario! I talked it up so much that the girls at the bookstore are all going to buy a copy! Congratulations!!

Preordered from my local indie bookstore. Eager to pick it up on Tuesday, or whenever they clear snowmageddon off our roads.

Congratulations, Susan. How very well done!

Love Kleenex and I am getting my copy as soon as possible. Congrats! Hope the ice melts soon.

I have your book on pre-order. Im very excited to read it!

History of Kleenex? I’m in. 🤧

So timely! Congratulations!

Library requested!

pre-ordered and looking forward to it. The changing impact of illness has been a topic of family discussion since you first posted about the book.

Looking forward to reading this!

this looks good. my mother passed in 2025 after we cared for her for 25 yrs. I work as a chaplain: we need honest conversations about these issues!! and we need better policies!!

Ah, to be called ‘winsome’ by the WSJ! Well done! I look forward to reading this.

Preordered and can’t wait!

Wow. Sounds like you wrote another great book.

As a healthcare worker who deals with bacteria on a daily basis, I cannot wait to read this. I pre-ordered it, and I’m just waiting for Audible to tell me it’s ready!

Congrats on the new book!

For this am in,a must read for me,I have always believed and knew so at least logically.

Well, we've now gone from 23 inches of snow to 5 inches of snow and 1.5 inches of ice. I would so much rather have the snow. Bracing for impact. (The last time we had that much ice, about 20 years ago, the power was out for two full weeks and we ended up boiling the Christmas turkey on top of the wood stove. It was so very, very pale and sad.) ... See MoreSee Less

6 days ago

That ice line keeps creeping northward. Now in northern DE we are getting less snow and more ice. I’m with you; I’d rather have the deeper snow and skip the ice. On the up side, up in north central PA, the fire companies are working on building the Eagles Mere toboggan run! I still smile when I remember taking our boys there. When we got to the bottom, about 1/4 mile onto the lake, the littlest looked around and asked, „Are we on the North Pole, Mommy??“ Pure magic. I don’t think it’s ready for a week or so yet, but at least something good is coming from the cold weather!

Unfortunately the ice is looking like a huge problem for many from your area to Texas. Hoping you had a cha nice to check some of my posts and it helped explain why there was an unusually high amount of uncertainty with this forecast.

1998. Epic!

Yep. It stinks. I actually AM looking forward to reading stories by oil lamp light though. We loved doing that all those years ago. Of course, I have adult children who probably aren't interested in "The Bears on Hemlock Mountain" these days but I won't let that stop me. 😅

Wood stoves are the best you will have heat and can still cook on them. Done it for a long time. Brings back great memories

Not a boiled turkey!!! 😭🦃 So thankful you had something to eat, though. The memories are fun, too! 🥰

That is a scary amount of ice. We Michiganders are not afraid of snow. Our youngest went to university in the U.P. and cross country skied to classes in the winter. But that much ice can have very scary consequences! Hugs to Virginia. You also aren't set up for it like Mich is so you have many more folks at risk.

Expecting a similar amount of snow and ice here in the southwest corner of NC.

Our forecast has been consistent at around 18 inches of snow. We will see. (I'm imagining a little more than that based on where we are located in the mountains).

Thank goodness I made it from the Adirondack Mountains to Florida in time. Be careful!

Stay warm and safe!

Exactly! Ice is so awful.